#32: Solaris

Director: Steven Soderbergh

Cast: George Clooney, Natascha McElhone, Jeremy Davies, Viola Davis

Introduction Plot Summary Impressions Wrap-up

My rating: Class A (3/7, hot white star). A stylish, moody psychodrama—serious science fiction—which hits hard and engages the attention on (at least) two levels. Expect to leave the film wondering what exactly happened…it won’t be satisfying for everyone, certainly, as it’s neither a thriller nor a romance—which is what the advertising for the film hinted at. Instead, it’s a deeply disturbing, thought-provoking film.

This is the third film directed by Steven Soderbergh to star George Clooney—the first two were Out of Sight and Ocean’s Eleven. The film was produced by James Cameron, and it’s based on a novel, Solaris, written by the Polish Stanislav Lem, who may be the most widely read science fiction author in the world. It’s the third time the novel, published in 1961, has been filmed: first for Soviet television in 1968 and again in 1972 in the form of a critically acclaimed Soviet film.

By any rights, this one should have been a blockbuster.

That isn’t quite how it worked out. The film, which cost about $47 million to make, grossed only $30 million, half of it in the United States, at the box office. Some have hypothesized that the trailer, which implies that the film is a science fiction romance with elements of a thriller, raised expectations amongst theater-goers which were not met.

The film, when viewed on its own merits, is a stylish if moody and intense psychodrama which explores themes of communication and epistomology—what we know and how we know it. It’s a serious film, and that may be why it didn’t do all that well. But it’s also a very good film, well worth watching and evaluating on its own merits.

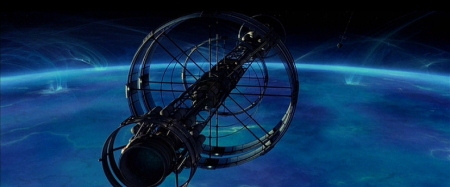

Short summary: Space station Prometheus, in orbit around an object named Solaris, stops communicating with Earth. Boy rides to the rescue of the troubled spacestation Prometheus in orbit around Solaris. Boy finds only two surviving members of the science mission, both clearly troubled. He dreams of his dead wife, and wakes up with her at his side. A series of flashbacks to Chris’ life on Earth with his wife Rheya, and her suicide, parallel his investigations on Prometheus and his time with Rheya. The visitors are projections of Solaris, and the survivors work out a way to destroy them so they can return to Earth without being followed. Chris elects to stay behind as Prometheus is absorbed by Solaris, and is reunited with his dead wife—or maybe not. Something happens, but as with much of the film, what that is, exactly, is a subject for some debate…

I won’t give you any more than that on this one. Thematically and cinematically, I suspect this film needs you to come to it with as few preconceptions as possible.

This movie is absolutely gorgeous: while the sets are either on Prometheus or in a series of very ordinary places on Earth, Soderbergh’s attention to light and shadow (as well as color) elevates the movie into the status of art. The film might even qualify as chiaroscuro. This quality gives the film a visual impact which was absolutely unexpected. The way that the camera lingers on the individual characters’ faces, often half-lit so that part of the face is obscured and part is well-lit, packs a visual punch which emphasizes the characters—and that the people are the real story.

The music is an electronic score which works well with the film, and it’s somewhat reminiscent of the band Tangerine Dream and their Love on a Real Train which appeared in Risky Business. It’s not intrusive, but it does further the sense of mystery and hidden events in the film.

The film uses a non-linear approach to story-telling, but it does so in a way that makes plenty of sense. Once Chris arrives on Prometheus, he dreams of his dead wife—and we get flashbacks of their initial meetng, as well as aspects of their life together. There’s always a blackout before a flashback starts, so it’s pretty easy to tell what’s going on as long as the viewer pays attention.

There is one character in the film that can’t talk, and that’s Solaris itself. No one ever calls it a planet, or identifies what kind of object it is, but it’s surrounding by shifting colors which look like some kind of heated plasma. It may be a planet, or a star of some kind, or something even stranger, but the important thing about Solaris is that it’s changing throughout the film. At the opening, its colors are cool blues, but as the film progresses the colors change until, at the end of the film, it’s reddish-orange. There’s no explanation of the change; maybe it does that all the time, and maybe it changed in response to Kelvin’s arrival. At any rate, the effect is hypnotic and striking.

There is one character in the film that can’t talk, and that’s Solaris itself. No one ever calls it a planet, or identifies what kind of object it is, but it’s surrounding by shifting colors which look like some kind of heated plasma. It may be a planet, or a star of some kind, or something even stranger, but the important thing about Solaris is that it’s changing throughout the film. At the opening, its colors are cool blues, but as the film progresses the colors change until, at the end of the film, it’s reddish-orange. There’s no explanation of the change; maybe it does that all the time, and maybe it changed in response to Kelvin’s arrival. At any rate, the effect is hypnotic and striking.

Clooney’s performance is solid and work-manlike; the script doesn’t give him a chance to show too much of his character, largely because he’s so badly damaged. To the film’s credit, that isn’t immediately obvious; at first he simply seems like a driven workaholic who feels a certain degree of detachment. When he discovers his now-alive dead wife lying next to him after his first night on Prometheus, other aspects of Kelvin become obvious: he deeply loved his wife, he didn’t really know her at all, and in the wake of her death he’s been shattered. Clooney’s Kelvin is numb to the wonder of what he’s seeing and experiencing, until he wakes up next to his now-living wife. Then he’s afraid, and subsequently so enchanted with his second chance that he can’t see anything else.

Clooney’s performance is solid and work-manlike; the script doesn’t give him a chance to show too much of his character, largely because he’s so badly damaged. To the film’s credit, that isn’t immediately obvious; at first he simply seems like a driven workaholic who feels a certain degree of detachment. When he discovers his now-alive dead wife lying next to him after his first night on Prometheus, other aspects of Kelvin become obvious: he deeply loved his wife, he didn’t really know her at all, and in the wake of her death he’s been shattered. Clooney’s Kelvin is numb to the wonder of what he’s seeing and experiencing, until he wakes up next to his now-living wife. Then he’s afraid, and subsequently so enchanted with his second chance that he can’t see anything else.

One word of warning: the movie is rated PG-13, but its initial rating was R. That’s because of Clooney’s butt. You’re going to see rather a lot of it, and for some people, that’s an attraction. Thematically, it’s about intimacy, but it’s there.

Natascha McElhone is really quite good as the suicidal wife and as the projection of her. She’s beautiful, yes, but she’s also by turns serene, troubled, confused and angry. Never anything less than completely truthful, she nevertheless conceals hidden depths. Viola Davis, as Dr. Grant, is an angry, scared woman, and Davis does a nice job of bringing that to the screen. But it’s Jeremy Davies, as Snow, the other survivor, who really steals the show. His frantic gestures and fidgeting convey that there is something very wrong with him—which is, of course, only natural given what’s happened on the station.

Natascha McElhone is really quite good as the suicidal wife and as the projection of her. She’s beautiful, yes, but she’s also by turns serene, troubled, confused and angry. Never anything less than completely truthful, she nevertheless conceals hidden depths. Viola Davis, as Dr. Grant, is an angry, scared woman, and Davis does a nice job of bringing that to the screen. But it’s Jeremy Davies, as Snow, the other survivor, who really steals the show. His frantic gestures and fidgeting convey that there is something very wrong with him—which is, of course, only natural given what’s happened on the station.

“What’s happened on the station” is frankly never very clear—something which suits at least one of the themes of the film. Snow tells Kelvin that if he tells him what’s going on, he won’t really know what’s going on, and that’s certainly true: even after it becomes clear that something about Solaris is creating projections of people out of the scientists’ memories, we don’t know why or how. The scientists hypothesize that the projections are made out of subatomic particles and stablized in some unknown manner; they further theorize, and subsequently prove, that a beam of anti-Higgs bosons will destroy the projections (for what it’s worth, the theorized but undiscovered Higgs boson is actually its own antiparticle, so “anti-Higgs bosons” don’t actually exist, even if the Higgs itself does).

Thematically—and here there are some spoilers, though I’ll try to be gentle—the film addresses a few interesting questions. First, it deals with how difficult it would be for us to understand and communicate with a higher order intelligence, especially one with god-like powers. The Solaris object is certainly godlike, though it’s (almost) never couched in mystical terms; in fact no one can tell what the heck is going on…But the film also touches on just how difficult it is to communicate with and understand ordinary human beings, as well. It’s clear that Chris didn’t understand the troubled and unstable Rheya, to the sorrow of both of them. A little more understanding, and their personal tragedy might have been averted. Of course, we can never really know the people we love, or so the film seems to say.

Thematically—and here there are some spoilers, though I’ll try to be gentle—the film addresses a few interesting questions. First, it deals with how difficult it would be for us to understand and communicate with a higher order intelligence, especially one with god-like powers. The Solaris object is certainly godlike, though it’s (almost) never couched in mystical terms; in fact no one can tell what the heck is going on…But the film also touches on just how difficult it is to communicate with and understand ordinary human beings, as well. It’s clear that Chris didn’t understand the troubled and unstable Rheya, to the sorrow of both of them. A little more understanding, and their personal tragedy might have been averted. Of course, we can never really know the people we love, or so the film seems to say.

The film also deals with the question of identity. Chris interacted with the Rheya he perceived, possibly without touching the real Rheya and her needs. One of the Rheya projection’s issues is that she understands that she’s a creation out of Chris’ memories. She isn’t a real person—she’s the person Chris remembers, and that’s a problem for her. The identity question is reinforced by the situation that Snow finds himself in.

It’s possible to interpret the ending of the film as a spiritual one—indeed, one of the Wretched Excess Crew made precisely that interpretation. Another interpretation is that Chris dies, and Solaris copies him and Rheya and allows them to live together in some sort of simulated reality. Solaris might have sent a duplicate of Chris to Earth, as well. Or it could be that the ending fell anywhere in between these two possibilities, including that Chris somehow rejoins the Rheya simulcrum in Solaris and lives happily ever after.

It’s a good movie—not a great one, but a good one, with some interesting philosophical underpinnings. It’s still a talk-oriented, cerebral psychodrama, and some people will find it boring. But if you’re interested in a good story about a couple who’s made terrible mistakes, and tries to take a second chance, set against a backdrop of an unknowable, powerful alien entity, try out Solaris.

There are a lot of differing views of the film, so I’m giving you a laundry list of other viewpoints.

Other Blog Entries and Reviews of Solaris:

Pinnland Empire’s take, and a comparison with the 1972 film

One interpretation of the film

A negative review from the Sci Fi Movie Page

Solaris explained on the Christian Sauve website

The Gods of Filmmaking review

Two Guys One Movie review

1000 Misspent Hours review

Solaris discussion questions from Philosophical Films

September 19, 2011 at 12:46 pm

Tarkovsky’s film version is far superior….

September 19, 2011 at 5:47 pm

I haven’t seen the Tarkovsky film (that’s the 1972 Soviet version, for those following along at home). Here’s what I know about it: it’s a longer film, almost twice the running time of Soderbergh’s version, and it’s much more…faithful is perhaps not quite the right word, but perhaps similar to, the novel—which is now on my reading list, for what it’s worth. At any rate, my understanding is that thematically and in terms of plot, the 1972 film is much deeper. I’ll get to it at some point, if for no other reason than it’s #19 on the MSN list. I’m simultaneously looking forward to it and dreading it 🙂

September 19, 2011 at 8:55 pm

Lem hated both version. I’ve read Lem’s novel — both films are drastically different. But yeah, Tarkovsky’s is much deeper — I guess you’ll find out soon! It’s one of my favorites….. If you can tolerate an “art house” foreign film with a glacial pace 😉